I arrived in Yosemite in October 2018 with one thing on my mind; soloing a big wall. In fact, this monkey had been on my back for months and life couldn’t go on until I’d done it. Friends in The Valley had wanted to climb together but I had done my best to avoid them. Nothing against them of course; a strawberry blonde 5.12 crack climber with a trust fund and low self-esteem could have offered me her soul and I would have been too busy constructing my poop bucket to notice.

My first day back in The Ditch (that’s what really cool people call it) I wanted to practice some wall climbing skills; with only a handful of aid pitches under my belt and zero hauling experience I was not exactly competent. I went to a popular crag and found a popular route to blockade.

The practice pitch went well. I mean, I did blow a cam hook and factor two on my daisy chain also attached to a hook, but it held and I didn’t even weight the rope which I believe is simply called a “dab”. Anyway, I really just wanted to practice hauling which it turns out is as simple as pulling on a rope, who knew?

I picked an objective and decided to start climbing the next day.

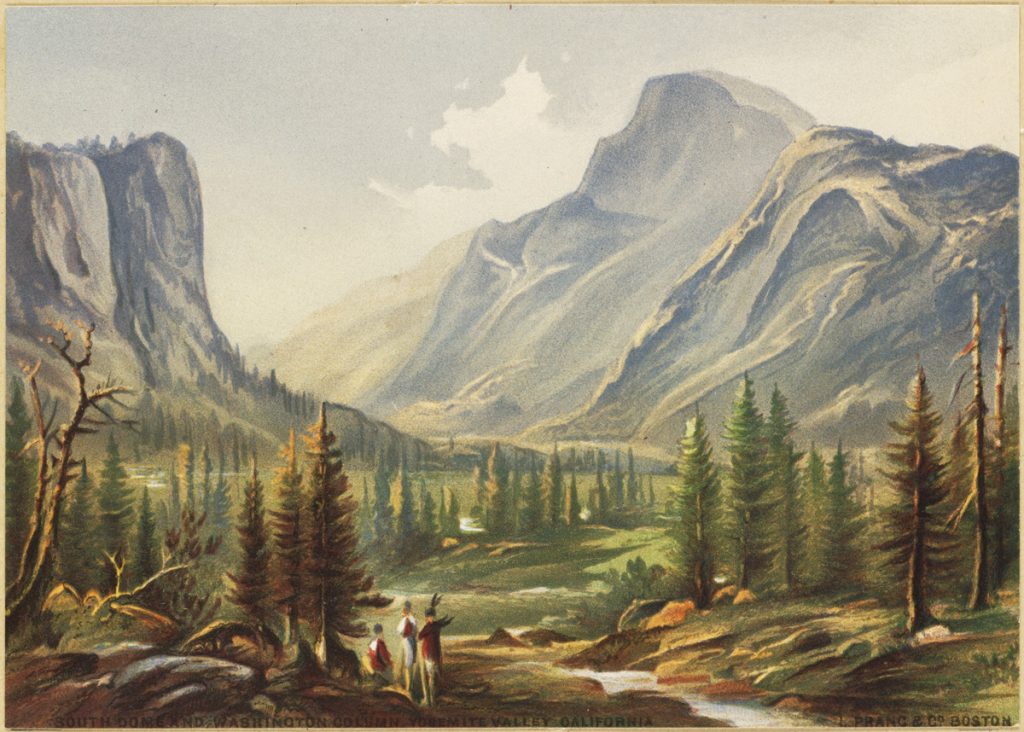

Washington Column is located at the eastern end of the industrialized valley directly across from Half Dome whose sheer 2000 foot face reminds you that you’re climbing a pebble.

The South Face is a popular first “big wall” route, and I use that term loosely. At 11 pitches and a generous 1,200ft it only just deserves its Grade V rating and is smaller than many Grade IV’s. Granted it requires slower aid climbing and has a large ledge that lends itself nicely to a night spent on the wall.

Having done quite a bit of rope solo free climbing in the past, including The Casual Route (IV, 5.10a) on Longs Peak and a 4.5 hour ascent of the East Buttress (IV, 5.10a) on Middle Cathedral, I was confident that I could climb the route in a single day, however I wanted the experience of sleeping on a wall, hauling a bag, and sipping coffee on a ledge, so I opted for a two day ascent.

I spent the morning jamming aluminum, nylon, water, and calories into the haulbag until it was roughly human sized. When I lifted it onto my back for the 45 minute approach I felt downright offended.

“How dare you burden me so?! I climb 5.12, dammit!”

The bag promptly began tenderizing my hip flesh which, as far as I can surmise, is the only demonstrable result of big walling. On the way to the cliff I bumped into a packless couple hiking down after checking how many people where on their route of choice. Huh. That struck me as a pretty fricken novel idea. How many people would be on the South Face? Was I about to enter a total gong show? My panic was quickly assuaged when the fore thinking couple told me the South Face was empty. Wait, what!? Empty? One of the easiest and most popular wall climbs in the valley? My sudden stoke carried me to the base of the route as I counted my lucky stars.

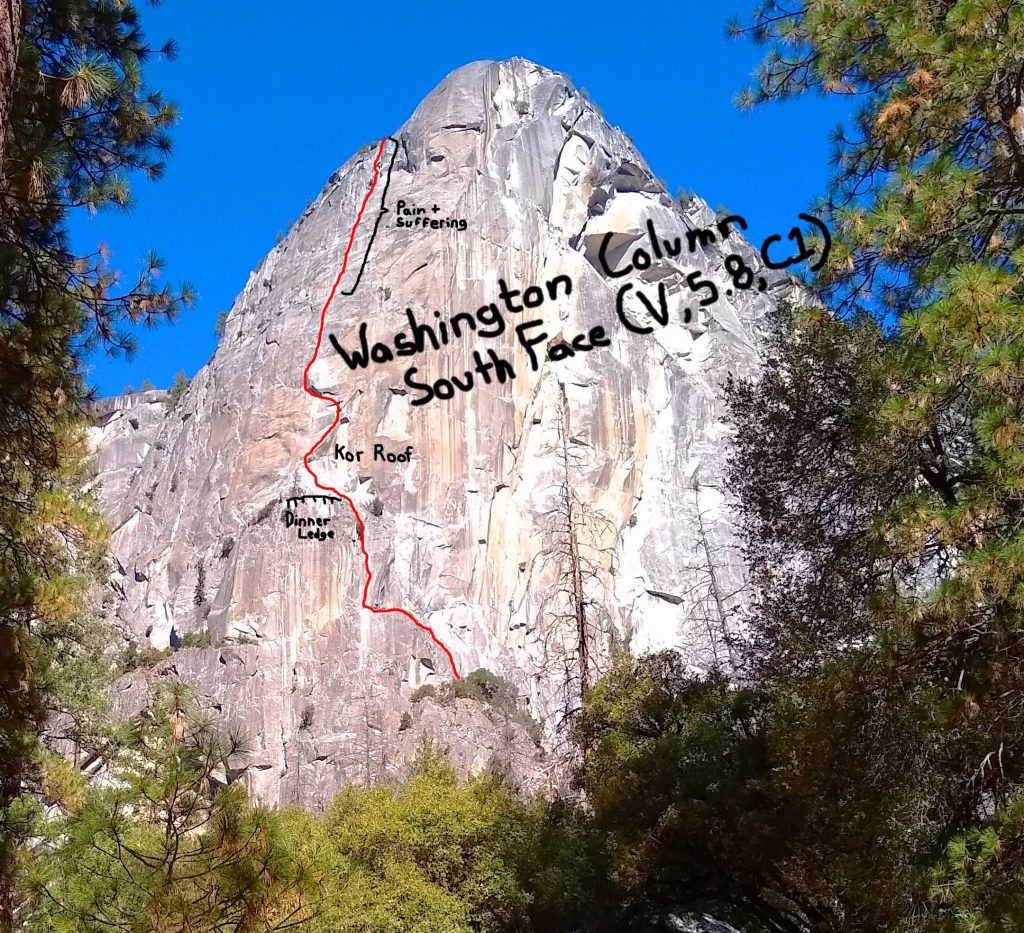

I started climbing around 3pm with only 3 pitches to Dinner Ledge, home for the night. I was hoping to make it there and lead one additional pitch before fixing the rope and rappelling into bed. This would leave me a digestible 7 pitches of climbing for day 2; and by climbing I mean climbing, rappelling, jugging, and hauling.

The first pitch of the route required some insecure 5.8 corner climbing and an easy traverse to a ledge. Pitch 2 was an aid pitch with a grade of C1. All my previous aid climbing had been on random free climbs, so this was the first pitch of aid I’d ever climbed with an actual rating. It was very easy; the routes I’d practiced on must have been significantly harder…

At the anchor I bumped into two middle aged climbers, Kent and Ed. So much for a lonely ascent. They had come to climb something else, but after finding it packed with parties had decided to divert to Skull Queen which shared the first four pitches with the South Face. I waited until Ed began jumaring the 5.8 third pitch up to Dinner Ledge and followed quickly behind him, deciding to climb in my approach shoes to show that I’m a total stud and that, should it come down to it, I should pass. Unfortunately, while I wrestled the reluctant haulbag Kent had started leading the next pitch above the ledge, the infamous Kor Roof, with plans to leave their rope fixed until morning. That was my plan.

This left me in no rush as it would soon be dark and I couldn’t start the next pitch with them already on it. I reached Dinner Ledge, spacious and flat, rolled out my ¼ inch foam mat and sleeping bag, and ate some soup while chatting with Ed and taking in the beautiful views of Half Dome, the eastern valley, and dusk’s first stars.

Kent struggled a bit with the lead: a 5.6 crack to a bolt ladder through a roof where some straining over the brink gets you into a crack that traces horizontally above the lip like a thin moustache. He stopped the pitch short and rapped back to the ledge on the haul line, leaving all the gear in situ.

I was hoping he would clean the gear on rappel, which would have made their morning easier and left the crack clean for me to jump ahead. Noting my chagrin they assured me they would get up at 5am and be out of the way.

“No worries, I’m sure as hell not getting up that early.” I replied.

Satisfied with the day’s work we chatted as the air cooled and the stars brightened. Ed negotiated with Kent to give me a precious beer. I turned off my alarm, expecting to hear them in the morning, and went to sleep.

I woke up not from the rustling of carabiners and packing of bags as I’d hoped but from a full night’s sleep. It was 7:30am and not a creature was stirring. Ed and Kent’s rope and gear still fixed in the crack above. I made the world’s noisiest oatmeal and coffee, ate, drank, and had my bags packed while the guys slowly put their mountain of equipment together.

I was at their whim; I needed to finish the route that day and realized the silliness of them pushing ahead of me with their four days of provisions. I sat and waited, resigned to my position in line. I should have brought more coffee, but things could have been worse.

By 8:30am they were almost ready to start climbing when a team of two popped up on our ledge. They were here for the South Face. My heart sank when I saw that they didn’t have a haul line, meaning they were doing the route in a day and would soon ask to pass me.

Ed and Kent hurried their preparations as tension built on the ledge.

“They stopped at an intermediate anchor. I’ll lead all the way through and then you guys can come up behind.” I suggested, breaking the silence but ignoring the obvious.

“Don’t you think we should go ahead?” They rebutted.

Checkmate. Of course they should. Soloing is slow; each pitch I have to cover the same ground three times, make 4 transitions, and haul a bag. A partnered team covers the same ground twice and does 2 transitions.

Still, I hesitated.

“We’ve climbed the route before and are going to short fix.” They added quickly.

Short fixing is a speed climbing tactic in which the leader, upon reaching the anchor, pulls up some slack before fixing the rope, and then continues leading on this loop of slack while the follower jugs.

Finally I conceded my place in line, went to shit in my bucket, and practiced waiting.

Three lifetimes later it was my turn to climb. I fired up the crack, swung through the free hanging bolt ladder, and made a strenuous reach to clip a piton in the moustache crack. I leapfrogged two cams across the traversing crack, passed Ed and Kent, and made it to the true belay. With the bag simply resting on the ledge below I was able to haul it with my bodyweight as I rappelled and cleaned the gear. This left me with a straight, simple jug to the anchor. Slick.

Back on top, I restacked the ropes. The Dayers where half a pitch above, Kent and Ed a half pitch below, and no one else was in sight. Time to climb!

The next pitch required a couple bolt moves over a small roof to get into a left arching crack. I backcleaned the entire crack except for any fixed gear, risking a big fall if a piece blows, but ensuring a quick, easy clean. I met up with one of the Dayers at the belay.

“How’s it going up there?” she yelled nervously to her leader as she saw me approaching.

I fixed the rope, rapped to the lower anchor, released the haulbag, wished Kent and Ed a good climb, and ascended away. When I reached the anchor the Dayer was still there. I was happy to be right on their tail but could tell that my presence was making it hard for them to feel like bad ass speedsters. We chatted awkwardly as I hauled and restacked the ropes.

I started leading behind the jugger. Up a crack, another leftward arch, a small overlap, and another vertical crack. Just before the belay was a mandatory 5.7 free move around a corner. Gardening gloves and blown out approach shoes made this feel pretty committing, but with the Dayer watching from a few feet away I held my sniveling.

“I’m impressed that you’re free climbing in gardening gloves.” she said as I pulled onto the small ledge.

“No big deal, wanna go out?” I did not say.

I rapped, cleaned, and hauled. The Dayer was already jugging away when I returned. I reorganized the ropes, which had become quite the chore. Both my haul line and lead line where not only the same color but the exact same rope. This is less than ideal when dealing with tangles and also facilitates making a deadly mistake. But hey, work with what you got.

The next pitch was the last pitch of pure aid I would be doing and was quite long at 150 feet. It was straightforward but I began running out of gear near the top, requiring me to use some sub optimal placements. I had brought less than half the gear the guidebook recommended. I made it to the anchor as the Day follower began free climbing away.

“Goodbye forever.” I whispered softly to the breeze.

After rapping, cleaning, hauling, and restacking I got into free climb mode. There were four pitches to the top; however, being a total boss, I decided to link them into two super long pitches. I was happy to switch to a faster climbing style and, although pretty tired, felt like the route was in the bag. I would top out in daylight, find the way down as dusk fell, and then spray to some tourists by nightfall.

That’s not quite how it worked out.

The first long link wasn’t too bad; some strenuous 5.9 jamming, some chimney climbing, and a step out right to bolts and thinner cracks up to the anchor at a tree. Long pitches make for long hauls and when I finally had that bag up there it all hit me. Dusk hit me. Dehydration hit me. “Fuck. This.” hit me.

It was about time I started to struggle. This climb had been too easy, too straightforward. But here I was- hating. And the hating hadn’t really yet begun.

Now would be a good time to mention that most people climbing the route leave their haulbag on Dinner Ledge atop pitch 3, and then rappel back after pitch 10 skipping the last pitch. That way you avoid 8 pitches of hauling, an entire pitch of struggle, and hiking down with a haul bag. That’s most people. I knew about this method. But for me-it wouldn’t cut it. I was practicing for bigger fish. I wanted to haul every pitch. I wanted to learn, but more importantly I wanted to brag about doing a real ascent and shit on proud climbers on the internet who had taken the easy way.

I’m glad I didn’t skip what would turn out to be the money pitch. Sure, the Kor Roof is stellar – if you climb to have enjoyable experiences, that is. But if you climb because of a deep self loathing you can’t quite shake, so that one day, you might trick your brain into deciding you aren’t a total waste of humanity – then the last pitch is downright spiritual. Otherwise it’s completely heinous.

Looking at the topo and doing some exhausted math my last pitch would be 65 meters. My ropes where both 70 meters. 65 is a smaller number than 70. Confident in my flawless logic, I set off. The climbing began enjoyably enough, some easy aid up a crack and into a corner led to a simple traverse and up to a couple fun, overhanging 5.8 moves past some trees. Then began the infamous 5.6 kitty litter gully, a low angle “U” shaped groove containing lots of sand, some lose blocks, and me. Rope soloing requires that you bring the slack rope up with you in some way. I had been dragging it up the wall so far, an effective method on clean rock, but the loose gully would require me to coil it up and carry it. So there I was: gardening gloves on hand, heavy rack around my waist, rope around my neck, stemming up a stucco halfpipe, 80 feet over any pro, in the dark. My headlamp at the belay below.

In this way I scraped and dragged my way up. Sweating through my shirt, sucking in deep breaths of still warm air; I saw the anchor tree just ahead. Now on flat-ish ground I took half a step. My belay device locked up on the rope, holding me back. I manually disengaged the cam and tried to step again. The rope pulled down my harness, digging it deeper into my hips and twisting it against my raw skin.

“WHY!?” I shouted into the dark, along with plenty of profanity.

Looking down I saw that I had run out of rope. My belay device was jammed into the backup knot, without which I would have dropped the rope down the pitch.

I looked around for a crack or seam in which to build an anchor but couldn’t find much in the crappy rock. Pulling against the rope like a draft oxen, gritting my teeth as puss seeped from my hips, I could just barely reach a small, irregular crack, between a rock slab and the mountain. I stabbed in a cam and attached the taught rope with a long cordellete. The relief on my hips was damn near orgasmic. I finished building the anchor and was psyched to have a rope fixed to the top. This ensured completing the climb; it wouldn’t be easy, but most of the risk and uncertainty was behind me.

I took all the unnecessary gear off my harness and rappelled. As I tiptoed past loose blocks and weaved around the occasional bush or tree limb, I realized this monster pitch would be unsafe, if not impossible to haul. Upon reaching the belay I decided to ascend the pitch with the haulbag instead of dragging it up after me.

Ascending a rope with a heavy pack on your back is stupid and any climbing book will tell you not to. Eventually your core muscles lose the fight with gravity, the pack flips you over, and you die. Or something like that, the books never really get that far. I’ve tried it before with a 100lb pack and it was horrible in every way so I thought I’d try it again, just for kicks.

It didn’t work. Maybe next time.

I relocated the haulbag to hanging from my harness between my legs. Although this was excruciating on my hips it let me use leg muscle to “squat” the bag up as I progressed on the rope. With each squat the bag would swing away from me and then slowly, but forcefully, swing back. The carabiner attaching the bag to my belay loop would mash into my harness-mashed genitalia.

“Awesome! I love it!”

I had already reached a sort of masochistic climax and was impervious to pain. Or so I thought.

As the bag swung back for the 10th time the connecting carabiner opened, the nose hooked my flesh, and the bag swung away…

“AHHHHHHHHHHHH!”

The rock ignored my gurgling, gasping, whimper-screams as I tried to discover the source of sudden and excruciating pain. Lifting the haulbag, I was able to unclip it from my ballsack.

I slumped against the rope, groaning. Minutes passed until I was ready to move again.

I shut the screwgate on that goddamn carabiner and then proceeded to let it swing into my swelling bro-varies 500 more times as my soulless physical form continued up the rope.

When I got to the bottom of the sand gully I switched to free climbing with the unwieldy haulbag on my back. I coiled both the haul and fixed line as I went, chucking the rats nest ahead of me in the runnel as I progressed.

Reaching the anchor I threw down the haulbag, sat on it, slipped off into the dirt, and laid there a while.

Eventually I started organizing the tangled 140 meters of identical rope. Stuffing the coils into the bag I looked up and sorrowfully remembered that I had cut the last pitch short and was not yet at the top of it, let alone the top of the formation. It’s not over.

Leaving everything behind I scrambled up slabs of granite to the actual top to suss out where to go and how to get there without falling 1000 feet to the valley floor. A couple spots required insecure climbing on sand covered rock.

After climbing back down to the gear I had a decision to make. Uncoil a rope, climb back up, fix the rope, rap back down, then climb back up with the haulbag; or, I could just throw the top heavy bag on my back and scurry my way up the sketchy slab; unprotected, exhausted, and apathetic.

One is easy, fast, and risky. The other tedious, slow, and safe.

I really didn’t want to put in the extra effort. But I also didn’t want to die. Not on 5.3 anyway.

I used the rope, made it to the top without incident, and fell asleep.

The morning was bright and indifferent to the night’s adversity. Somehow, so was I.

When my thoughts turned from self congratulation to self preservation I started hiking down. I needed water, food, and human interaction. I had soloed a big wall. Now I could chill out, climb with friends, and go track down that strawberry blonde…

2 Responses

This was awesome. I bailed my first bigwall, it was skull queen, last month. Thats why im reading this. Is there a video of you ranting, sir?

Sorry I missed this comment, glad you liked it! Mostly just mumbling… Did you end up sending something? I was out in the valley this November as well.