I tiptoe away from the anchor, onto a slab, toward a blank corner and the steepest bit of rock we had yet encountered. I urge myself;

Climb like you know how: place good gear, move confidently.

A thin seam begins on the slab and lures me into the vertical. I find myself clawing at dirt before mashing my fingertips into the excavations and twisting until the grit bites the tops of my fingernails.

Keep climbing, rest will come.

A few moves later I’m pumped silly with toes smudged into a shallow corner on bearings of sand.

You’re cruxing! Place gear!

I wiggle a cam into my previous finger pod, the stem sticks straight out like a perch too sketchy for a swallow. I clip it.

Get another piece!

I dig with the nut tool, covering my quaking feet with expelled grist and uncovering only a wrinkle in the hard stone.

Shit!

A glance upward suggests no respite.

Don’t fall!

I clip into the cam at my waist and commit to it slowly as my fingers open, pulling straight out with my knees braced against the rock. It holds.

Phew! Breathe.

Blood drains out of my forearms and pressure squeals out my ears.

“This piece isn’t very good,” I begin as the cam rips out and I fall long enough to wonder;

Did I place anything else?

A solitary #0 cam held firm, as did Noah, the fall so far that I was now well below him — at least, that’s what I tell some people. “You good?” he asked, “Yeah,” I said as I swung back to the belay, “Let’s try that again.”

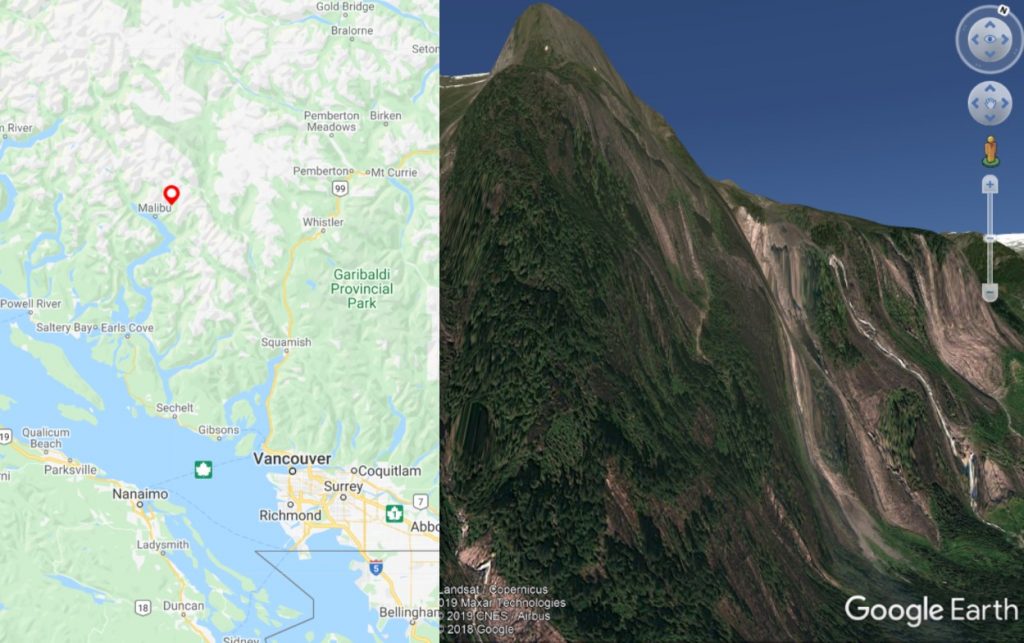

Neither of us had done a big wall first ascent before. Nor a small wall for that matter. Nor a second, third, or tenth ascent. In fact, neither of us had so much as set a gym boulder, yet we found ourselves clinging to the side of the biggest unclimbed wall I happened to find during my virtual flights through Google Earth.

Princess Louisa Inlet in Canada’s British Columbia hides a 4,600-foot castle of moss and granite that we besieged not like knights: brave, noble, skillful, but as jesters: ignorant, chaotic, foolish. Knights had come before us and failed, perhaps we fools could access the Princess’s Court atop the wall?

Before we had climbed a single foot we had already missed multiple boat rides, forgotten gear, gotten lost, hurt ourselves, woken up in a river, crawled along fresh grizzly tracks, eaten rotten garbage, and smoked half the trips whiskey.

“Even if we don’t climb anything this is totally worth it.” Noah offered one evening after another routine, yet fruitless session of scheming and plotting. “Totally.” I replied, unconvinced.

Noah was an obvious partner; we had cut class together in high school, climbed together in Yosemite, and sought adventure to make sense of it all. His excitable “Cut twice, measure never” nature the perfect yin to my typical “Measure only” yang. Together we formed one complete and utter fool.

The American Alpine Club supported our folly through the Live Your Dream Grant, which I would rename the Eat Your Words Grant. We imagined the review committee snickering at our grandiose proposal, meager experience, and bright optimism only approving our application in delight at the absolute beat down we would surely endure. Luckily, Noah and I are quite capable of laughing at our own stupidity, pain, misfortune, and obscene banter doing so frequently and hysterically.

Once established at the base of the wall we fought over the binoculars, chattered breathlessly, and pointed in every direction as we scanned for something to climb. We sought a queen line; elegant and improbable, a canvas for our brushstroke. Ideally, a continuous finger and hand crack through otherwise blank rock leading to a slightly overhanging headwall and an all-points off dyno to the summit jug, where Princess Louisa herself would be waiting.

Instead of hand cracks and strong, independent women, we found dirty faces, bushy cracks, mud choked corners, and buttresses weeping bile. It was junk – but it was our junk – and therefore the raddest shit we had ever seen. Beyond the muck, we spotted a clean buttress way up high and quickly decided to focus our efforts on reaching that patch of stone.

When we finally did start climbing we were delighted to discover we were decent rock climbers- terrible strategists, food planners, outdoorsmen, and human beings generally; but decent climbers and splendid fools. We made solid progress on that first day and climbed four low angle pitches to a large ledge before anchoring our ropes and rappelling back to camp on the ground. We spent the evening patting each other on the back and drowning our hard-earned humility in a bath of sugary whiskey.

“Dude, we can do this in a day.”

“I’ve climbed ladders harder than this.”

(a couple of swigs later)

“EAT MY DICK ALEX *brrpp* HONNOLD!!!”

We spent the remainder of the trip choking on those pompous words.

Beyond that ledge, the rock steepened to nearly vertical and elicited the whipper described above. The climbing was a mix of free climbing unaidable, shallow, dirt-packed, finger-tip flares and aid climbing perfect hand cracks running with water and walled with quagmire. We would often climb ourselves into a dead-end, runout over micro cams or expanding pitons, and eventually downclimb back to relative safety, absolutely frazzled, utterly demoralized, and wondering why we didn’t finish college.

Pitch 8 the dirtiest Pitch 11 clean rock dirty cracks

Each lead took over two hours regardless of if it was aid or free, short or long. During that time the belayer had long enough to recover from his lead and become bored senseless. He’d reach the belay and snatch the rack from the whimpering sack of flesh he had once called a friend, then lead out until he too was sobbing or soiling himself.

In this way we made progress. Each morning we ascended our fixed ropes, got shat on until dark, then rappelled back to the ground, licked our wounds, and heroically filled out a book of children’s crosswords.

After eight days of such efforts and one-third of the way up the wall we ran out of fixed rope and faced the decision; ditch the umbilical cord and commit fully to the wall, or, go home. Our remaining time was tight so Mother Nature had her say too and we waited for one last weather forecast. Good weather meant we could go for it, commit to the chaos and take the test. It meant failure was our own. A bad forecast meant the trip was over, pats on the back, “We tried our best”, “If only…”, it meant secret relief.

The forecast was good, there were no excuses yet I could come up with plenty. We packed nervously, buttoned-up camp, and ascended the fixed ropes for the last time before untying them and hurling them back to the ground keeping just what we needed. Retreat was now a daunting task.

The mood was tense as we set up for the night on the two perfectly sized, perfectly flat natural ledges of granite about 1000 feet off the deck. Was I doing this because I wanted to or because we planned to? Did I fear simple discomfort or actual harm? How did Noah feel? Not brave enough to answer any of these questions, I went to sleep feeling spineless and woke to a brief rain shower before the clouds danced away impressively.

The next two days were spent dropping gear, breaking a harness, taking whippers, ripping pieces, screaming obscenities, and having the absolute time of our lives. We knew we were precisely where we ought to be and only worried about the next pitch and whether the rolling papers would last.

After 19 pitches we finally reached that patch of clean stone; except, it wasn’t. A few wide and chimney pitches led to the second crux of the route, a vertical 6-inch off-width corner crack walled with moss. My lead.

On a low-gravity day, after a long sleep, and a cup of real coffee I’d probably still fall off of this thing. After 12 days and 2,800 feet of toil, I didn’t stand a chance, yet I needed to climb it without aid.

I laced up my shoes and grabbed our two big cams before wriggling into the crack and inching upward, compensating for my bad technique with maximal effort. After 100 feet I was empty; my hand-fist stack sliding out of the swampy maw, wringing water onto my rattling calf lock. I shrieked savagely with desire, exertion, vitality.

I fell and screeched some more, thankfully the bumped cam stuck to moss better than I did. I rested at the end of the rope before returning to my highpoint, clipping a nylon ladder to the cam that caught me, and mantled up onto a small, ant-infested ledge.

I was thoroughly shit-canned; Noah’s turn.

I had been insisting we were a pitch from the top since the day before but was now certain of it and happily handed the rack to Noah to take us there. The wide cracks ended and Noah managed some technical slab climbing on a tired mind before pecking his way up a fine, finger sized flare. The rope moved out and then back in before snarling echoed from above, out again, back in, then it stopped. He hadn’t made it.

As I ascended the rope to meet him I wondered what the next obstacle might be and delighted in the possible solutions; lasso the summit, stand on each others’ shoulders, skyhook toward oblivion? 11 days before I doubted we’d climb a foot of this behemoth, but in that moment, with thousands of feet below us, I was positive we’d make the top.

When I got to Noah he had relaxed from his lead and solved the final obstacle. After restacking the ropes he led up a short and filthy hand crack before an unprotected traverse around a blank headwall and into the dense forest above, disappearing from view. After some crashing and cursing he reappeared directly above and dropped a line for me to ascend and avoid the dangerous traverse.

We had done it. We were psyched, thirsty, and running out of daylight.

We haphazardly strapped our gear to our backs and stomped through the bush toward a symphony of glacial streams hoping to drink as honored guests at the Princess’ Banquet, however, our tower of rock offered no access in the increasing dark. With mouths drier than a serfs wineskin we found a solitary puddle filled with wriggling larvae, dead insects, and bacterial slime – a worthy chalice for fools we thought. Drunk on E. Coli we hooted, hollered, snapped some bad photos, and quickly found sleep on a fine, clear night.

Come morning we began our march off the mountain. A glance at a map weeks earlier indicated a straightforward 8 mile hike which we figured would be safer, quicker, and cheaper than rappelling down the monstrous face. Those “8 miles” of granite mazes, unexpected glaciers, and unconsolidated talus took us over 18 hours to negotiate. By the end, we were barely human and had spent the last 12 hours discussing revolting fetishes until they became appealing and utterly destroying our backs and knees. I am sure now, after months of reflection, a few doctor’s visits, and an MRI that rappelling would have been safer, easier, and much less expensive.

We returned to the dock of the small provincial park at the head of the inlet and admired our handiwork with a can of peaches and bar of chocolate we had stashed in the woods. The next morning we would hobble back up to the wall, break down our base camp, and retrieve our jettisoned ropes before catching our tour boat back to town.

The other folks on the boat, shocked by our scent and heap of gear, discovered our feat and congratulated us earnestly. The taste of celebrity quickly soured and I tried to convince them we had done nothing of worth; pursued a selfish goal for no one’s benefit, hardly even our own. Their bright eyes, perked ears, and excited chatter took no note of my cynicism. They asked every conceivable question except for “Why?”, because they knew the answer and the answer heightened their awe; no reason at all. The moments with these inspirited strangers are among my fondest memories.

“You could do it too,” I assured them, “if only you were more foolish.”

A Journey to the Center of the Earth (1000m, VI, 5.10+ C2) was established over 14 days. The wall is as we found it: no bolts where used, no anchors left fixed.

15 Responses

Love it man! You’re a true climber’s climber!

High praise bud!

Love it man. Smoke that whiskey

thanks dude!

What an epic! Nice work man. Very fun to read. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Cory! Hope you’re well bud

Exquisite wordsmithing my friend. Congrats on the epic FA! What’s next on the radar? 😉

Thanks bud! Have you heard of the SW face of Lone Mountain? 😉

Again – Congratulations. Great write-up.

Thanks Dad!

Many times, during the 6 years, I was training specifically for Ironman; I questioned why was I doing this? And that was even after I qualified. I will always remember the 100 days straight of over 100 degrees F that I trained in Tucson. It was drudgery and abuse. But looking back, now 31 years to when I finally did Ironman; I don’t regret it. In fact Roland and I are cycling every night now and being back on the bike is wonderful. Cycling is something one can do ‘into’ aging; sure hope I remember how to roll if I fall though… that won’t be pretty on brittle bones…. Love you – Mom

Badass Mom!!

Such a good read, thanks for sharing your foolishly adventurous expeditions with us all 😉 Hope all is well!

Epic adventure and story telling! Nice work boys, so rad!

Thanks a lot buddy!